Children Don’t Migrate They Flee Event at the American Red Cross

The photo exhibition Children Don’t Migrate, They Flee was featured at the American Red Cross conference Community Resilience: Evolving Perspective and Approaches to Migration from March 15 to 17, 2016.

A project of the Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking and Too Young to Wed, this exhibition includes photographs and commissioned assignments by award-winning photojournalists Katie Orlinsky, Kirsten Luce, Meridith Kohut, Estaban Felix, and Moises Castillo that portray the dire circumstances that compel unaccompanied children and families to flee their homes in the Northern Triangle in Central America.

ATEST is grateful to the Red Cross for sponsoring Children Don’t Migrate, They Flee, and for allowing us to share the work of these incredible photojournalists. You will see a small taste of their work and the story behind these images below, but we hope you will take time to view the entire exhibition here.

Merlit Melissa Nuñez Rodriguez, 6, who is fleeing with her mother and father to escape gang violence in Olancho, Honduras, in May 2014, looks at a mural of popular routes through Mexico painted on a wall at the migrant shelter Los 72 in Tenosique, Mexico. This shelter provides mats to sleep on, secondhand clothes, meals, basic medical treatment, and help in applying for immigration visas and refugee status for people traveling north. Photo by Meridith Kohut.

Through the powerful visual imagery they produced, Katie Orlinsky, Kirsten Luce, Meridith Kohut, Moises Castillo, and Esteban Felix have helped give voice to the thousands upon thousands of children and families at the center of a humanitarian crisis that spans from the Northern Triangle in Central America, through Mexico and to our border.

In 2014, tens of thousands of unaccompanied children and families from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador arrived at the U.S. border. For many children and families, this journey was rife with violence, exploitation and trafficking. The risks were so great, but they were more tolerable than what they’d been forced to endure in Central America’s Northern Triangle.

Sadly, this humanitarian crisis shows no signs of abating. 10,500 unaccompanied children crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in October and November last year.

And the root causes of this mass exodus—violence, corruption, poverty and a climate of impunity—remain unchanged and largely ignored by U.S. policymakers.

We hope this exhibition – which was on display in the U.S. Senate earlier this year – will help change that.

A four-year-old recent deportee stands outside her home in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, with her aunts in August 2014. Along with her mother, she attempted to migrate to the United States on August 7, 2014, but was apprehended in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico. Family members said they were both imprisoned and abused before being deported back to Guatemala. The girl’s mother continues to be unable to eat or speak after the experience. Photo by Katie Orlinsky.

Katie Orlinsky traveled in August 2014 to Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, where child migration rates are among the highest in the country. The four-year-old girl in this photo, walking with her aunts, had been recently deported from Mexico. Her mother had tried to migrate to the United States with her, but they were apprehended in Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico. Family members said they were both imprisoned and abused before being deported back to Guatemala. The mother was so traumatized, she wasn’t speaking or eating.

For many children and youth in Guatemala, leaving home and risking the treacherous journey to the United States is perceived as the only chance for leading a dignified life free of violence and fear.

As all of you know well, the US has a long history as a country of refuge for individuals fleeing violence. In 2008, Congress strengthened protections for this particular population when it reauthorized the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act. Today, unaccompanied children from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are afforded greater protections to ensure they are able to access humanitarian relief under our immigration laws.

Paula, who does not attend school, works washing clothes with her female family members in the town of Los Duraznales in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in August 2014. Deeply entrenched discrimination against women severely limits educational and employment opportunities for Guatemalan girls and women. The State Department reports a conviction rate of 1 to 2% for femicide, clear evidence that women and girls face a harsh climate of impunity with a government unwilling to offer protection from escalating violence. Photo by Katie Orlinsky.

ATEST believes strongly that these protections must not be rolled back. The situation is too grave to jeopardize children’s access to the relief that they deserve.

The UNHCR interviewed 400 children from the Northern Triangle and Mexico who had come unaccompanied across the U.S. Border for their seminal report Children on the Run. Nearly half of the Guatemalan children that the UNHCR interviewed were from indigenous groups.

According to the U.S. State Department, “pervasive discrimination” results in the marginalization of indigenous communities in Guatemala, and significantly heightens the risk of labor trafficking. They reported that in 2014, 39,000 children, primarily indigenous girls, worked as domestic servants and were often vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse.

Women and girls face severe insecurity. Deeply entrenched gender discrimination severely limits educational and employment opportunities for Guatemalan girls and women. Governments are failing to address these systemic challenges. Women and girls face a harsh climate of impunity. For example, the State Department reports a conviction rate of only 1 to 2% for femicide.

Family members show the clothes, laid on the bed of late seven-year-old Kenneth Alejandro Castellano Raudales, who was found tortured and murdered by the Mara-18 gang, according to local police. In the same week, the gang killed Kenneth’s 12-year-old brother, Anthony Castellano. The family lives in the La Pradera neighborhood, a Mara-18 gang stronghold in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The police report that seven children were murdered by Mara-18 gang members in this neighborhood in May 2014. Photo by Meridith Kohut.

In this photograph, taken by Meridith Kohut, family members have laid out clothing on the bed of late seven-year-old Kenneth Alejandro Castellano Raudales (Ra-oo-dal-ays), who was found tortured and murdered by the Mara-18 gang, according to local police. In the same week, the gang killed Kenneth’s 12-year-old brother. The family lives in a Mara-18 gang stronghold in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The police report that seven children were murdered by Mara-18 gang members in this neighborhood in May 2014.

The Raudales family is shown in this May 2014 photo in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. They mourn the loss of two young sons, ages seven and 12, murdered in the same week. Honduras has the world’s highest murder rate, and San Pedro Sula, with a homicide rate of 171 per 100,000 people in 2014, is the world’s most violent city. Photo by Meridith Kohut.

These photos convey the incredible pain and loss that so many families in the Northern Triangle experience every day. For them, violence is an inescapable fact of life.

Honduras has the world’s highest murder rate, and San Pedro Sula, with a homicide rate of 171 per 100,000 people in 2014, is the world’s most violent city.

Rates of violence in the Northern Triangle are among the highest in the world. Guatemala and El Salvador have a murder rate more than 800% higher than that of the United States. Meanwhile, Honduras’s murder rate is close to 1,900% higher than that of the United States. Family violence is hidden or met with impunity. These forms of violence are key drivers for children and young people fleeing.

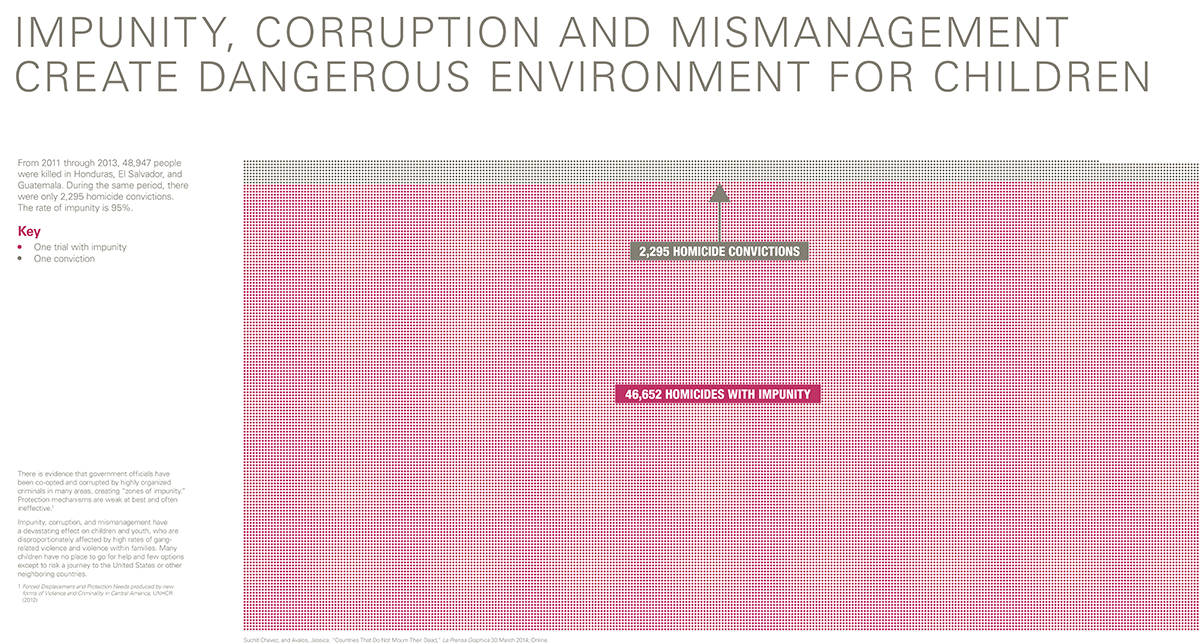

As this infographic shows, from 2011 through 2013, 48,947 people were killed in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. During the same period, there were only 2,295 homicide convictions. The rate of impunity is an astounding 95%.

Even worse, there is ample evidence that government officials have been co-opted and corrupted by highly organized criminals in many areas, creating “zones of impunity.” Protection mechanisms are weak at best and often ineffective.

What we know is that impunity, corruption, and mismanagement have a devastating effect on children and youth. They are disproportionately affected by high rates of gang violence and violence within families.

Many children have no place to go for help and few options except to risk a journey to the United States or other neighboring countries. That is why the United States must demonstrate leadership by not only protecting those refugees at our border who survive the treacherous journey north, but by pursuing regional solutions to address the root causes of the crisis in the Northern Triangle.

Two sisters and a friend from Honduras, ages 13, 14, and 16, arrive at a cattle ranch along the border between Guatemala and Mexico in July 2014, with their coyote, who is smuggling them to the United States to be reunited with their parents in Texas and California. The sisters have not seen their parents for six years, and their friend has not seen her parents for 12 years. While reunification with family members is a factor for many youth risking the dangerous journey to the United States, domestic violence, sexual violence, and other forms of gender-based violence – in addition to impunity for these crimes – are influencing the decision to flee. Photo by Meridith Kohut.

In this photograph by Meridith Kohut, two sisters and a friend from Honduras, ages 13, 14, and 16, arrive at a cattle ranch along the border between Guatemala and Mexico with their coyote, who is smuggling them to the United States to be reunited with their parents in Texas and California. The sisters have not seen their parents for six years, and their friend has not seen her parents for 12 years.

While reunification with family members is a factor for many youth risking the dangerous journey to the United States, domestic violence, sexual violence, and other forms of gender-based violence – in addition to impunity for these crimes – are influencing the decision to flee.

Fifty percent of girls interviewed by UNHCR after arriving at the U.S. border from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, reported abuse in the home as a factor that forced their migration. Because sexual abuse is an underreported crime, we know that the estimate of 50% is low.

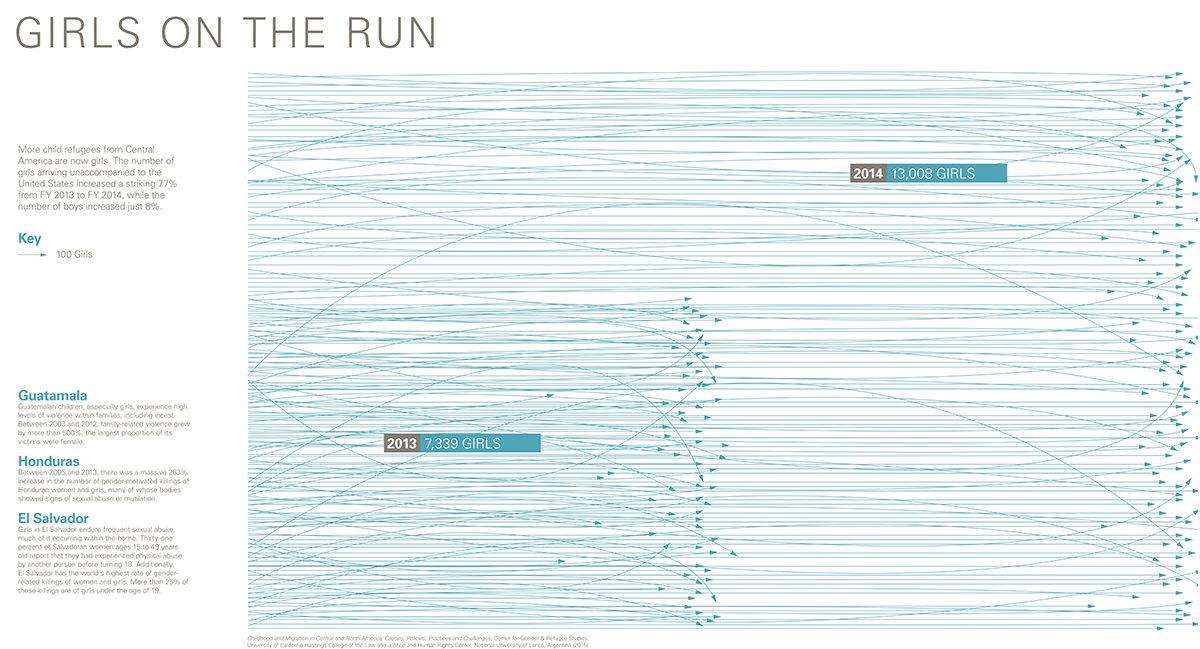

As this info graphic shows, increasingly, child refugees from Central America are girls. The number of girls arriving unaccompanied to the United States rose a striking 77% from FY 2013 to FY 2014, while the number of boys increased just 8%.

A joint report by the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies at UC Hastings and the Human Rights Center at National University of Lantos, Argentina, has revealed horrific trends:

- In Guatemala, children, especially girls, experience high levels of violence within families. Between 2003 and 2012, family-related violence grew by more than 500%, and the largest proportion of its victims were female.

- In neighboring Honduras, during roughly the same timeframe, there was a massive 263% increase in the number of gender-motivated killings of Honduran women and girls, many of whose bodies showed signs of sexual abuse or mutilation.

- Finally, in El Salvador, there are breathtaking rates of family violence reported: Thirty-one percent of Salvadoran women ages 15 to 49 years old reported that they had experienced physical abuse by another person before turning 18.

Men, women, and children journeying through Mexico are shown at the Los 72 shelter in Tenosique, Mexico, in April 2015. This shelter, run by Catholic priests and volunteers, provides mats to sleep on, second-hand clothes, meals, basic medical treatment, and help in applying for immigration visas and refugee status for men, women, and children traveling north. Photo by Katie Orlinsky.

This photo by Katie Orlinsky show men, women, and children journeying through Mexico who have stopped at the Los 72 shelter in Tenosique, Mexico, in April 2015.

This shelter, run by Catholic priests and volunteers, provides mats to sleep on, second-hand clothes, meals, basic medical treatment, and help in applying for immigration visas and refugee status for men, women, and children traveling north.

Sadly when the crisis erupted in 2014 the US did not invest its resources in shelters like Los 72, nor did it use its diplomatic influence to ensure that the Mexican government do as much. Instead, the disproportionate emphasis went to building Mexico’s law enforcement capacity to interdict children and families fleeing violence, making an already treacherous route that much more dangerous.

Border Patrol agent Christopher Hamer waits with apprehended migrants for transport vehicles on a ranch in Brooks County, Texas. Migrants walking here are avoiding the checkpoint in Falfurrias, Texas, along Rt. 281 North (background) to San Antonio in February 2015. Photo by Kirsten Luce.

Surviving the treacherous journey does not guarantee refuge. The U.S. Border Patrol reports that approximately 84,000 children were apprehended at the Southwest border during the FY 2014 and the first six months of the FY 2015. Of the nearly 80,000 removal cases initiated by law enforcement, the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute estimates that as of June 2015, over 15,000 children had been ordered removed.

Many of those children – nearly half of them – did not have access to a lawyer. Without a lawyer, the challenges are immeasurable – no one can expect a toddler to represent herself, a preposterous suggestion that one immigration court judge recently made publicly.

Indeed, comparisons show that children without representation only succeeded in 15% of cases whereas those with representation were allowed to remain in the US in 73% of cases. That is why it is critical that Congress pass the Fair Day in Court for Kids Act that was introduced in the Senate last month. The legislation would ensure kids have access to lawyers, legal orientation programs and post-release services.

Women and children from Central America are apprehended just after crossing the Rio Grande into Texas, in June 2014. In July 2014, Mexico’s National Migration Institute began to intensify interdiction efforts in southern Mexico by carrying out more mobile highway checkpoints and raids. Human rights advocates have documented the use of brutal tactics by Mexican authorities in enforcement operations, including pushing individuals off moving trains. Photo by Kirsten Luce.

This photo and the previous one were taken by Kirsten Luce. Here, women and children are apprehended just after crossing the Rio Grande into Texas.

The United States has stepped up border enforcement and supported Mexico to increase border security on their end. In July 2014, Mexico’s National Migration Institute began to intensify interdiction efforts in southern Mexico by carrying out more mobile highway checkpoints and raids. Human rights advocates have documented the use of brutal tactics by Mexican authorities in enforcement operations, including pushing individuals off moving trains. These counterproductive measures have undermined our long-standing commitment to protect refugees and ensure they have access to safe haven.

A woman sleeps in the processing center in Brooks County, Texas, in March 2015. Most detainees are from Central America, and most will eventually be deported. Casa Alianza, a Honduran non-profit organization that has been working with street children for more than two decades, operates the nation’s only intake center for deported minors. The organization has documented many disturbing stories of children who were deported after attempting to flee Honduras, including one of a 14-year-old boy who was killed two weeks after he was returned to his community, and a girl who was shunned and excluded by teachers and neighbors because of the assumption that she was sexually promiscuous during her journey out of Honduras. Photo by Kirsten Luce.

Treating this humanitarian crisis as an immigration and border issue decreased the number of unaccompanied children and families reaching our border since the peak in 2014 – but it has not diminished the danger and vulnerability experienced by the children and families fleeing violence in their home countries.

Offering refuge to persecuted migrants at our border is a core American value dating back to the protection of religious minorities in the colonial era, of political dissidents during the Cold War, and of refugees fleeing the violence of Iraq and Afghanistan. Detaining refugees, particularly women and children, is a stain on our country’s celebrated legacy of offering safe haven. Investing more to support regions to address the root causes of forced migration is a more sustainable and cost effective solution.

Isaura Ortega and her baby Cafemin pose for a portrait at a migrant shelter in Mexico City, in April 2015. Isaura was forced to flee her home in Guatemala City because of threats of extreme violence. Isaura’s family owned a grocery story in Guatemala City, and in 2008 criminals began to threaten the family. Gangs killed Isaura’s sister and brother – and kidnapped another sister – because the family refused to pay an extortion fee. When family members fled to Mexico, Isaura stayed behind because she was pregnant, but she soon decided it was too dangerous and made the journey to join her family. Photo by Katie Orlinsky.

When you explore the exhibition, you will see four portraits with stories of the horrible violence that is pushing children and families to flee their countries. Here, Isaura Ortega and her baby Cafemin pose for a portrait at a migrant shelter in Mexico City.

Isaura was forced to flee her home in Guatemala City because of threats of extreme violence. Isaura’s family owned a grocery store in Guatemala City, and in 2008 criminals began to threaten the family. Gangs killed Isaura’s sister and brother – and kidnapped another sister – because the family refused to pay an extortion fee. When family members fled to Mexico, Isaura stayed behind because she was pregnant, but she soon decided it was too dangerous to stay in Guatemala City so she made the journey to join her family.

Isaura and the others photographed in the portraits are representative of the thousands of children and families that have arrived at our border with the hope of safety and security. We must stand with them.

Romina Alonso Lorenzo, 12, left, and Isabel Alonso Lorenzo, eight, at their aunt’s home in Concepcion Chiquirichapa in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, in August 2014. Romina and Isabel are two of four orphan sisters; their 14-year old sister has recently fled to the United States where she works to help support their family. The other sisters live with their aunt in a crowded two-room home. Photo by Katie Orlinsky.

As mentioned before, ATEST undertook this project because we hoped that the images and stories of what’s really driving unaccompanied children and families to cross our border would inspire more conversation, more compassion, and more proactive humanitarian leadership by the United States government.

Instead of battling a perceived immigration crisis at our border, the U.S. government should address the forced migration of children by investing in stronger child protection systems, by strengthening rule of law to reduce the climate of impunity for perpetrators of gang and family violence, and by fostering regional solutions that address the root causes of violence and insecurity.

It is also critical that provisions of the Trafficking Victims Prevention Act designed to ensure legal protection for vulnerable unaccompanied children, who may have been trafficked into the United States, are not weakened or eliminated. As recently as last week, there were efforts to do as much. Fortunately a concerted effort by congressional champions and a broad coalition of advocacy groups defeated those harmful measures. More opposition will undoubtedly be necessary.

Instead of introducing harmful legislation that jeopardizes children’s lives, Congress needs to pass legislation like the Fair Day in Court for Kids Act to ensure children and other vulnerable immigrants have lawyers to help them navigate the complexities of the immigration system.

In addition, the Administration must also show leadership. It must ensure that children in their care are provided with comprehensive services and reunited with family members to care for them. Detention is unacceptable.

Finally, there is a great need for resources. Not only should Congress and the Administration provide adequate services to unaccompanied children and their families in the United States, they must address the root causes of this crisis.

We hope you will join ATEST and the other incredible organizations working to shine a light on the children and families from Central America who deserve our compassion, not our condemnation.

It is the strength, resilience and determination of mothers like Isaura that inspire me to act. We hope you will find inspiration in the exhibit as well. Together we can change the narrative about this crisis, turning away from the emphasis to date on security and border enforcement, and turning to humanitarianism and compassion.